6. Non-Linear Programming (NLP)#

In this chapter, we will extend what we have learned about optimisation problems to situations where the objective function and/or at least one of the constraints are non-linear functions. First, we will learn about the necessary and sufficient condition for the optimal solution of non-linear problems, without and with equality constraints. For this, we will look at the classical economic dispatch (CED) as a nonlinear problem (NLP). Beyond analytical tools that help us find optimal solution to such problems when they are of limited complexity, we will present some algorithms that allow to solve more complex problems with many degrees of freedom numerically.

6.1. The Classic Economic Dispatch revisited#

We learned about linear optimization in the previous chapter 2.1, with the example of economic dispatch, which we can model as a linear optimization problem. To do so, we had to abstract from a lot of real world detail to be able to define the problem with a linear objective function and constraints is a stark abstraction. However, many things in real world energy systems are not linear. For example, the efficiency of a power plant may depend on its production level, rather than being constant, which means that the amount of fuel used for the production of one unit of electricity depends on .

[!Extra] Extra task: Think of other aspects in the simple economic dispatch model which could be non-linear in a more realistic model.

In words, the economic dispatch problem introduced in chapter 2.1 is: minimize total production cost such that the power balance constraint is satisfied. So far, we assumed the marginal cost of production to be constant, i.e. independent of generation level

[!Example] Consider a company running two power plants, given their cost function, which contain quadratic terms:

Suppose the company has to supply a total power of 1200MW over the next hour. If the company decides to run both plants, each at 600MW, what is the marginal cost for each plant? Remember that the marginal cost at a given generation level is the derivative of the cost function.

Instead of running both powerplants at the same power, the company might decide to solve the economic dispatch problem to minimize the total cost. This can be formulated as a non-linear optimisation problem, in this example with quadratic constraints.

More generally, both constraints and objective may be non-linear. We require the functions

[!Example] A simple nonlinear optimization problem is

, which can be solved analytically. Generally, to find extremal points of any such function

, we need to find for which the derivative, hence solve . After that, we need to determine if a given extremal point (there might be more than one!) is a minimum or maximum. To do so, we evaluate the second derivative at the extremal point. If , we have minimum, if , we have a maximum.

Notice that the example above does not even have a constraint. In the realm of linear optimization, such a problem would mostly not be very useful, because a linear objective function without constraints is unbounded and thus has no optimal solution. A linear problem needs constraints to have an optimal solution, and if it has a optimal solution it always lies on a constraint. For non-linear problems, both of these are not necessarily true: For a nonlinear function without additional constraints, an optimum can exist, and the optimal solution of an NLP may not lie on any constraint.

Analog to the 1-dimensional example above, we can find stationary points of higher-dimensional functions. Similarly to evaluating first and second derivative, we inspect the Gradient

and the Hessian

Evaluate the gradient to find stationary points.

Get the hessian

Evaluate it at the stationary points

Get the eigenvalues Remember that we find the eigenvalues of a matrix

To characterize the extremal points using the Hessian, look at the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix. Apart from minimum and maximum, you may have saddle points.

Eigenvalues |

stationary point is |

||

|---|---|---|---|

Strictly convex |

positive-definite |

all |

minimum |

Convex |

positive-semidefinite |

all |

minimum (may be more than one) |

Concave |

negative-semidefinite |

all |

maximum (may be more than one) |

Strictly concave |

negative-definite |

all |

maximum (may be more than one) |

indefinite |

some positive, some negative |

saddle point |

|

TODO: Why necessary and sufficient conditions for the optimality? |

[!Example] Suppose we want to minimize

. To do so, find the points where the gradient is zero, i.e. solve

Next, inspect the Hessian tbd

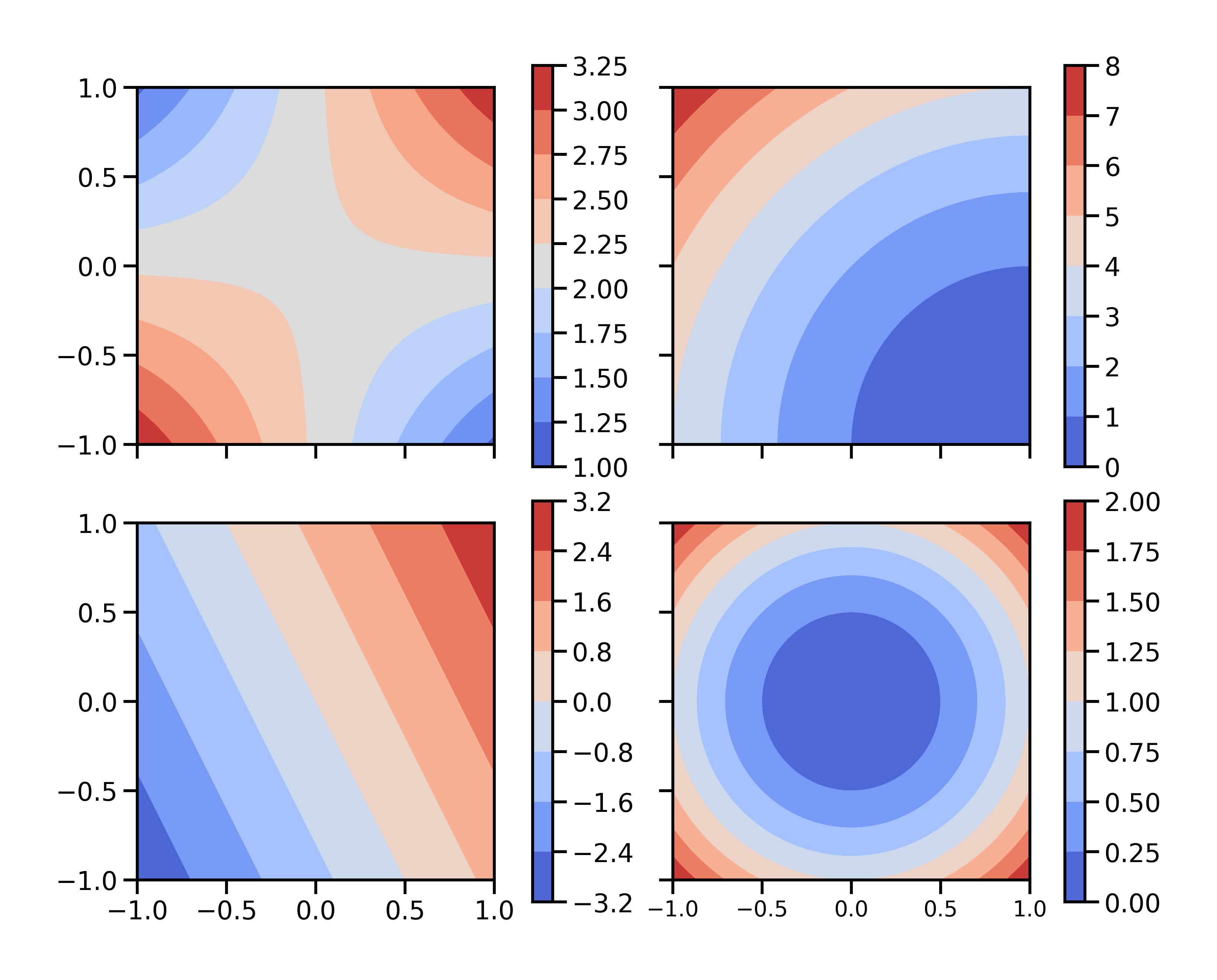

Look at the following contour plots visualizing functions in 2 dimensions. Which of these are linear, which are non-linear? How many minima, maxima and saddle points do you see, and where are they?

Fig. 6.1 Contour plots for four different functions

6.2. NLP with constraints#

So far, we have considered problems without any constraints. To analyse problems with constraints, we need some more ingredients.

Necessary conditions for a minimum with (non) linear constraints c(x).

We know: shadow prices can be calculated for an active constraint in linear problems.

Active constraints: Equality or inequality constraint which is satisfied as

Lagrangian:

with the Lagrange multipliers

Necessary conditions for optimality

[!Example]

Write down the Lagrangian

First partial derivatives need to be zero

The optimal value of a Lagrange multiplier

Example CED

All power plants operate at the same incremental costs equal to the Lagrange multiplier. This holds true in this example, where only the balancing equation holds. Other constraints can play a role, e.g. constraining the operation of the powerplants, which may have an influence.

Example only equality constraints.

Back to the initial example: Power plants do produce at different marginal cost, which indicates that the operation is not optimal.

So far, we have practiced to minimize cost functions. Does that mean that for the real energy system, we should minimize the cost function? No! We are interested in social welfare.

We are after social welfare

Economic dispatch with elastic demand. How many degrees of freedom? n (number of power plants) + m (number of consumers). Marginal cost is equal to the marginal utility.

Optimality conditions for problems with inequality constraints: Karesh, Kuhn and Tucker (where Karesh was writing a master thesis on this) extended the formalism to problems with inequality constraints.

Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions

KKT

Necessary conditions

For larger problems with many more degrees of freedom, an analytical solution can become difficult. Be aware that being familiar with the analytical methods can help to understand numerical results. Thus, it makes sense to understand the more simple examples well.

6.3. Solving NLP numerically#

There are many algorithms for numerically solving NLP.

Gradient descent: Start somewhere, make a finite step into the direction of the steepest descent and repeat from there. Other methods use higher order derivatives to decide how the algorithm proceeds. Depending on where you start, you might end up in a different optimum.